5 Regulatory Perspectives

In addition to the technical challenges encountered during the design and implementation of in situ remedies, environmental statutes and their implementing regulations may also pose obstacles to the implementation of in situ remedies that make success more uncertain. The goals of this section are to identify statutory and regulatory challenges and to suggest ways to address them to improve the chance of success.

5.1 Statutory Challenges

Site cleanup activities are governed by multiple statutes and regulations. Many remediation sites are regulated under either the federal CERCLA or RCRA processes along with state requirements. Sites that do not fall under federal CERCLA or RCRA oversight are regulated solely through a state or local regulatory process. Additionally, federal requirements mandated by the Clean Water Act (CWA) and Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) may apply, depending on site conditions and the remedial approach.

Specific CWA requirements that may be applicable to in situ remediation include, but may not be limited to, UIC permits and antidegradation policies and requirements. SDWA requirements may apply to proposed amendments that have the potential to cause exceedances of primary or secondary drinking water standards (e.g., MCLs).

Each state may have specific regulations governing the placement of amendments into the subsurface. State regulations may limit the types and quantities of amendments; require permitting, approval or contingency plans; or prohibit some types of hydraulic fracturing. States may also have anti-degradation policies. Various county or city ordinances may also apply.

Federal, state, and local requirements may add time to the approval and implementation of the cleanup process but are meant to ensure the protection of human health and the environment. A thorough review of all site-specific permitting and regulatory approval requirements is necessary before preparing plans to implement or modify in situ remedies.

An understanding of potentially applicable requirements early in the cleanup process is critical to timely approval and implementation of an in situ remedy. When an in situ technology is first identified as a viable remedial option, communication between stakeholder, practitioner, and regulator is needed to identify what submittals are required prior to implementation (that is, UIC permits). Timely communication with the regulatory agencies overseeing the cleanup will assist with regulatory compliance and regulatory and stakeholder acceptance.

5.2 Traditional CERCLA Site Cleanup Process

5.2.1 Historical Process

CERCLA, later amended by the Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA), and its implementing regulation, the National Contingency Plan (NCP), established the CERCLA process for addressing potentially contaminated sites. Although cleanups under RCRA differ somewhat, the process for National Priorities List (NPL) sites (whether the cleanup is led by the federal government or a state), as well as for many state programs, is often applied to complex sites where in situ remediation is used.

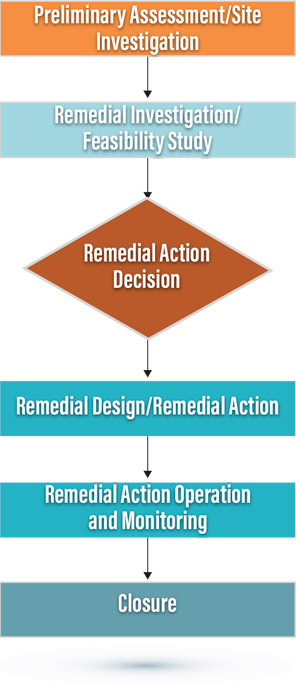

The CERCLA traditional process is largely linear, starting with preliminary assessments, and if a site is listed on the NPL, continues with site investigations, remedial investigations, and feasibility studies. Once a need for remediation is determined, several technologies are evaluated. The record of decision (ROD) documents the selected remedial technology and approach. This process is shown in Figure 5.1.

Early actions can also occur at any point in the process. These include emergency responses or interim remedial actions. Early actions are meant to reduce risk quickly, control groundwater plume migration, or facilitate site reuse (USEPA Memorandum “Use of Early Actions at Superfund National Priorities List Sites and Sites with Superfund Alternative Approach Agreements,” 8/23/19).

Figure 5.1. Traditional regulatory processes.

However, the overall process generally follows a linear order of tasks meant to result in a final site cleanup.

If the initial approach to cleanup specified in the ROD is not effective or feasible, remedial options can be reevaluated and then modified in a Record of Decision Amendment (RODA) or Explanation of Significant Difference (ESD). This process to document remedy changes, while needed for many reasons, can cause significant delays in completing cleanup.

With respect to in situ treatment, the remedy in a ROD or RODA may be too specific. For instance, decisions may have specified the amendment, method of delivery, or both. In these cases, if during design or implementation a change in either of these remedial approaches is identified, it would require a time-consuming change to the decision document.

A more effective approach could be to select a more general class of remedy, such as ISCO in general rather than a specific oxidant. Although the feasibility study would base the evaluation of ISCO on the performance data for specific oxidants used at other sites, the selection of the amendment could be made in design. Similarly, the application method can be left to the design phase rather than described in the decision document. Also, depending on the uncertainty associated with an in situ approach, the decision can include a contingency remedy that has been fully evaluated and could be used in lieu of the first remedial choice.

One way regulators try to mitigate the risk of an ineffective remedy is to require a high threshold of information before a decision is made. As discussed earlier in the document, optimizing the application of in situ remedies is complex and requires iterative testing and adjustments within the individual steps, such as remedy design. In situ treatment pilot test results, or initial monitoring of a remedy, may show that the original amendments or delivery method were not functioning as expected. The challenge is allowing sufficient flexibility in the remedy decision to develop an appropriate in situ approach while allowing for the uncertainty of success through contingency strategies.

To advocate for a more flexible approach to the remedy in a decision, convey to the regulator and other stakeholders the iterative nature of the design and operation of in situ remedies, particularly those using amendments, This communication could occur during review of an in situ treatment proposal (work plan) that includes the iterative testing and implementation process described in Figure 1-2. The need for later revisions will be minimized if this iterative process is built into the decision and implementation documents. These documents can be flexible with respect the amendment, amendment dose, or delivery method.

5.2.2 Survey Results

The ITRC In Situ Optimization Team developed a survey (Appendix G) to identify regulatory challenges to implementing in situ remedies. The survey was widely distributed to ITRC members. The purpose of the survey was to determine how many in situ projects the respondents had been involved in, evaluate the rate and root causes of why any of the proposed projects were initially not acceptable to the regulators, and identify common reasons for this occurring. The ultimate goal was to find areas where regulatory impediments could be addressed to help reduce uncertainty in implementing in situ remedies.

Although the survey results showed that practitioners and regulators review about the same number of in situ proposals, the regulators were approximately 40% more likely to deem the first submittal as incomplete.

5.2.2.1 Reason(s) for Incomplete Submittal Determination

5.2.2.2 Root Cause(s) for the Inadequate Information Provided

5.2.3 Challenges with the Traditional Regulatory Approach and In Situ Treatment

The interpretation of the survey results in Section 5.2.2 indicates that regulators generally want more information to support an in situ remedy than is often provided by the practitioner in the first submittal. In the traditional approach the regulator tries to mitigate risk by requiring a high threshold of information needed before a decision is made. Frequently the regulator would require more investigation, bench studies, and/or pilot testing to refine the CSM and demonstrate that the proposed remedy is more likely to be successful than other remedial technologies.

This process would lead to a very specific description of alternatives that would then be incorporated into the site’s decision document. The implementation of these highly prescriptive decision documents often become drawn out because administrative changes to a decision document are difficult and time-consuming. To overcome delays, regulators and practitioners should:

- identify decision points in the process when consensus on a path forward makes sense within the context of Figures 1-1 and 3-1 within the staircase diagram, define where regulator review/approval is required under a given program (that is, necessary or decision document and final full-scale Remedial Action (RA) following bench/pilot)

- use the general technology proposed (that is, in situ remediation), but specify actions that must be done to address uncertainties (for example, need pilot test)

- consider which “boxes” in Figures 1-1 and 3-1 require public notice

In 2018, EPA’s Office of Superfund Remediation and Technology Innovation issued a memorandum to Superfund national programs managers USEPA Superfund Task Force #3: Broaden the Use of Adaptive Management. The purpose of the memorandum was to provide a working definition of “adaptive management” and to outline an implementation plan to expand the use of an adaptive management process at Superfund sites to improve and accelerate the cleanup process.

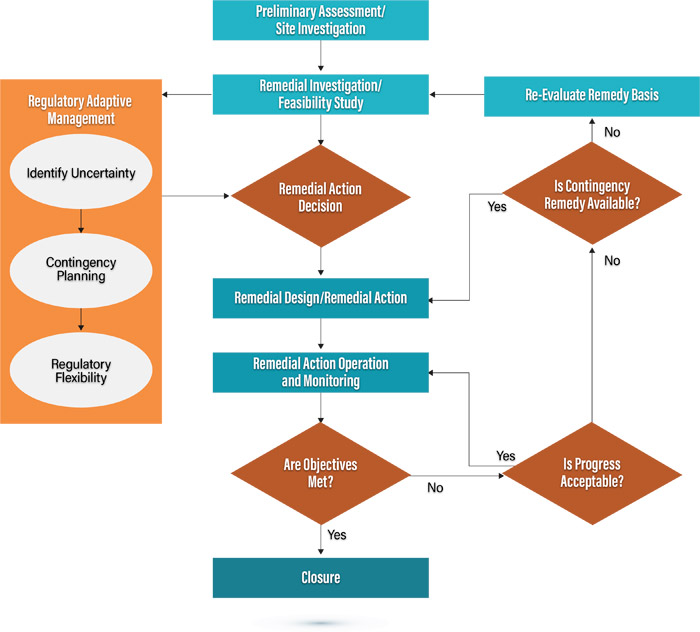

Figure 5-2 shows how an iterative process similar to that discussed in Sections 1, 3, and 4 (see Section 3.1, Implementation and optimization staircase) of this document can be used in the regulatory approval process for in situ remedies.

Figure 5-2. Regulatory adaptive management.

Understanding that the successful application of in situ technologies is an inherently iterative process, that the regulatory process can allow for iterations within the traditional regulatory process, and that the early and close coordination of all stakeholders is essential, it is possible to optimize the regulatory process by building needed flexibility into a project’s decision documents.

The goal of regulatory adaptive management is to transition away from the traditional high threshold of information needed prior to the decision document to a regulatory environment that identifies uncertainties and provides robust contingency planning within the decision document itself.

If the decision documents to be implemented acknowledge the uncertainty and develop robust contingencies during the planning process, decisions can be made with significant uncertainties as long as it’s clear how those will be managed and how decisions/changes in the remedial approach will be implemented.

When documenting the uncertainties and making contingency plans with respect to the use of different amendments, specific attention must be paid to the general type of amendment to be used (e.g., biotic (aerobic/anaerobic), abiotic (oxidizing/reducing), or a different kind of surfactant). If the change in amendment will change the geochemistry, different secondary effects (see Section 3.2.2) may need to be considered along with changes in the process monitoring (Section 4.4.1) A good example is moving from bioremediation to chemical oxidation or chemical reduction. This may require additional bench-scale testing. If well documented as a contingency in the original decision document, it may be possible to avoid additional authorizations and changes to the decision documents.

The amount of flexibility allowed in a decision document pertaining to the delivery of the selected amendment may also be constrained. For example, extraction and reinjection of contaminated groundwater can pose challenges, although (USEPA 2000) clearly stated that addition of an amendment that will result in treatment meets the requirement that contaminated groundwater be treated even if that treatment occurs after reinjection, or that hydraulic or pneumatic fracturing may not be allowable. Flexibility for the dosing of the selected amendment generally doesn’t need much documentation; it’s expected that additional rounds of injection are to be needed.

Click here to download the entire document.