3 Amendment, Dose, and Delivery Design

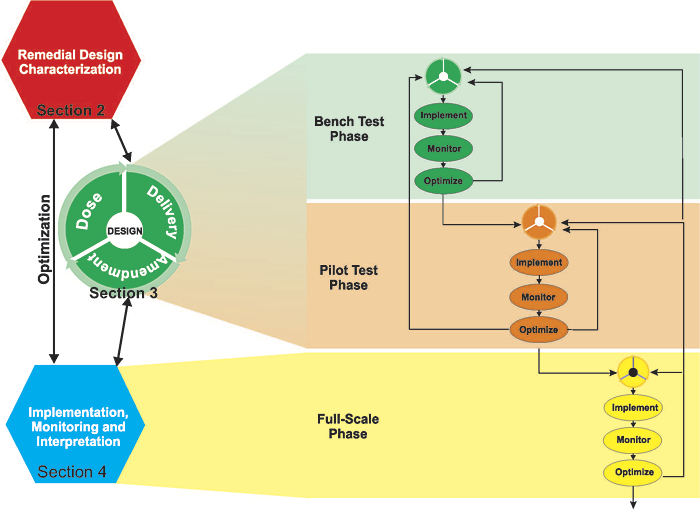

The remedial design process is commonly visualized as a linear sequence (see Section 5.2) that begins with the CSM; however, in practice, the overall in situ design process is iterative and cyclical with many feedback loops at any step connecting to both earlier and later steps (see Figure 3-1). Once the CSM is developed and RDC is initiated, one or more potentially viable remedial design options are identified. This remedial design consideration is a preliminary screening of potentially viable remedial alternatives considered relative to site characteristics and treatment objectives. A design is refined and further developed once the predesign investigation is complete, and the project moves to implementation. Each of these steps is an optimization step; every step in the sequence is evaluated and the results used to improve the process for the next step or used to justify returning to an earlier step in the sequence.

3.1 The Design Wheel and Optimization Process

The cyclical nature defined in Figure 3-1 is extended into the implementation phase of testing and monitoring. Refinement of the design following selection of the amendment and the delivery strategy may involve various tests, all applying the dose, delivery, and amendment design feedback; results of each test feed refinements into a subsequent test. The same applies to the full-scale implementation phase, in which operational testing as well as performance testing could result in modifications to the dose, delivery, and even the amendment. For instance, during full-scale implementation the monitoring results may indicate that repetitive dosing or more frequent dosing may be required to achieve optimum performance.

The design wheel involves consideration of the amendment, delivery method, and dose simultaneously throughout the in situ RDC, design, implementation, and monitoring process. Any step in the sequence can be performed again as new information becomes available. For example, during the initial evaluation of remedial design options, one or more data gaps may be identified in the CSM, and the overall process returns to improve the CSM before continuing evaluation of remedial design options. Similarly, during RDC, a site characteristic may be found to be unfavorable to the remedy under consideration, which necessitates returning to the consideration of remedial design options rather than moving forward to implementation.

Each of the steps in the stages of the optimization process (Remedial Design Characterization; Amendment, Dose, and Delivery Design; and Implementation, Monitoring, and Data Analysis; Figure 3-1) must also consider the nature of the in situ remediation amendment (e.g., liquid or solid), dose of the amendment (e.g., concentration, mass, or volume), and method of amendment delivery (e.g., liquid injection or slurry/solid injection). The nature of the amendment, delivery method, and dose are all interrelated by a cyclical process (Figure 3-1). For example, a certain amendment (e.g., an organic carbon source intended to stimulate reductive dechlorination of a chlorinated solvent) may be available in solid or liquid forms, and the liquid forms may be available in a range of concentrations. The selection of solid or liquid, and liquid concentration, in turn will affect how much of the amendment is required. The amendment may also be available in a range of viscosities or densities, which (along with the nature of the amendment as a solid or liquid, and the volume of the amendment required) may affect the method of amendment delivery. Amendment delivery options may, for example, include hydraulic or pneumatic fracturing, solid, slurry, or liquid injection via direct push methods, injection via temporary or permanent wells, etc. Thus, all three factors (amendment, dose, and delivery) are simultaneously and iteratively evaluated to develop a remedial design. Design is also implicitly considered in each stage of the remedial design sequence. For example, the data needed in the predesign investigation are determined in part by the amendment, dose, and delivery method under consideration, emphasizing the cyclical and iterative nature of the overall process. The elements of the Design Wheel (amendment, dose, and delivery) are considered further in Sections 3.4, 3.5, and 3.6.

Figure 3-1. Implementation and optimization process.

Figure 3-1. Implementation and optimization process.

3.2 Design Considerations

The following sections highlight some of the factors that need to be considered during the design process. Defining the TTZ is one of the essential first elements of remedial design. Consideration must also be given to how the selected remedy may affect subsurface conditions and the potential for secondary effects in other subsurface characteristics, in addition to the primary or desired effect. In certain situations, it may be appropriate to apply coupled in situ remediation technologies simultaneously or sequentially to effect treatment of sites (e.g., sites with contaminants in different geological units or with comingled contaminants). A final key component of the design that needs to be considered is the relationships among cost, risk, and certainty of outcome (USEPA 2016).

3.2.1 Target Treatment Zone

3.2.2 Secondary Effects

3.2.3 Coupled Technologies

3.3 Design Support Elements

This section describes the design elements that are used to support in situ remediation design. These elements are an extension of the CSM and RDC data (see Section 2). The number one source of failure for amendment injection to meet remedial treatment objectives is the lack of an adequately detailed lithologic characterization of the TTZ. A remedial design that minimizes uncertainty often includes a bench study to identify the proper amendment and dosing requirements. This is followed by a pilot study to understand injection rates, distribution pattern around injection points (ROI); (see Section 3.7.1 for a discussion of distribution vs. ROI), and any site-specific conditions adverse to amendment placement (i.e., tendency for amendment to daylight at the injection site or nearby locations) (ITRC 2017a). With these parameters properly understood, the greatest source of uncertainty and failure is the reliance on overly simplified subsurface conceptual models. Design elements used to support in situ remediation design include modeling/analytical tools, laboratory bench testing, and field pilot testing. Each is discussed in the follow subsections.

3.3.1 Modeling and Analytical Tools

Table 3-1 outlines some of the models that can be used to support in situ remediation projects, provides a brief description of the model, and a source for additional information. Some of the software is public domain and other models are commercially available and require a license. Spreadsheet tools have been developed by many practitioners to support remediation projects. Spreadsheets allow rapid iteration on the design of an in situ remediation program, e.g., assessment of injection duration over a range of flow rates, or calculation of possible lateral transport assuming cylindrical distribution as a function of volume injected and effective porosity. This list is not an endorsement for any of the models, and other models may be available beyond those that are listed here (ITRC 2011c).

Table 3-1 Models that can be used to support remedial design ▼Read more

3.3.2 Laboratory Treatability Bench-Scale Testing

3.3.3 Field Pilot Tests

3.4 Amendment Selection Considerations

This section offers descriptions of the main amendment types, target contaminants, typical delivery methods, and links to fact sheets from the Treatment Type column in Table 3-2. The fact sheets describe limitations of each amendment, the elements to consider that are design-specific, health and safety issues, references, and some case studies.

The selection of amendment(s) and injection technologies may affect each other and should be considered in an iterative process taking into account site-specific factors such as infrastructure and physical limitations, geology/hydrogeology, and client preferences or regulatory requirements as identified in the CSM. In addition, location of the TTZ (within the source area or the downgradient plume) should also factor into the amendment selection and dosing. The amendment selection information in this section is presented independent of delivery methods. In Section 3.8 (Delivery Strategies), delivery technologies are described and a matrix assists in the consideration of applicable delivery technologies based on site-specific conditions (see Section 3.8).

Differences in treating the source versus treating the plume are critical when selecting amendments. For example, in a source zone, for some amendments, you might consider injecting the amendment at a much higher concentration to deliver more of the reagent in a smaller volume and have a more aggressive treatment. By contrast, in a plume area, you might consider injecting the same amendment at a lower concentration but in a greater relative volume because distribution over a wider area is more important than delivery of a large dose to a small area.

Table 3-2 provides information about amendment types and is organized primarily by treatment processes and treatable contaminants. This allows a user, with a known list of target COCs, to access a suite of applicable amendments and screen out options that would not be appropriate for remediation of the COCs. For instance, a project designer who is looking to use in situ injection technologies to remediate dissolved-phase concentrations of benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene (BTEX) in groundwater can consult the matrix in Table 3-2 and immediately identify amendments, such as a peroxide compound or other oxygen delivery method, as being more effective than a vegetable oil-based product. The table also describes the function of each amendment (e.g., oxidation, aerobic degradation enhancement compounds, anaerobic degradation enhancement compounds, surfactants, etc.) so that the user can further evaluate the potentially applicable amendments and limit the options to those that provide an appropriate function. The table links to additional information (fact sheets) on suitability for remediating contamination in various media, suitability for treatment of various soil types, cost, expected active lifespan for the amendment, suitability with delivery technologies, advantages over other amendment types, and potential limitations of the amendment.

In many instances the use of a laboratory batch or column test should be considered during the amendment selection process, not only to inform the efficacy of the amendment for a particular project, but also to estimate potential remedial design parameters that will be further refined (e.g., pilot testing). Many amendments blur the lines between biotic and abiotic applications. The amendments are grouped under biotic, abiotic and other additives (Appendix A1 Biotic Amendment Fact Sheets, Appendix A2 Abiotic Amendment Fact Sheets, and Appendix A3 Other additives Fact Sheets), in what we believe are the primary applications, but recognize that any amendment may be considered in multiple sections.

Table 3-2. Amendment types and typical injection/emplacement technologies ▼Read more

3.4.1 Combined Remedies—Spatial and Sequential Remedies and Mixed Contaminant Options

3.5 Amendment Dose Requirements

Several sequential steps are typically required to estimate the amount of amendment that must be injected for any remedial design. Amendment dose here is used broadly to be applicable to volume, concentration, addition rates, and mass. Another consideration is the persistence of the amendment (e.g., electron donors such as lactate that are completely miscible with groundwater versus donors such as emulsified vegetable oil that stick to the geologic media and are dissolved/released slowly over time). The first step is to define the size (e.g., volume and contaminant mass) of the TTZ (see Section 3.2.1). The second step is to evaluate the background demand for the amendment, which reflects the amount of amendment required to establish and maintain the appropriate conditions for optimal remedy performance. The third step is to evaluate the target demand for the amendment, which reflects the amount of amendment required to destroy the target contaminant. An approach is outlined in this section to estimate the total amendment requirement for the TTZ. The amount of amendment required per injection point, or other distribution mechanism, is a factor of the delivery method, which is addressed in Section 3.5.3, and degradation kinetics for the amendment.

3.5.1 Background Demand

3.5.2 Target Demand

3.5.2.1 Examples of Amendment Requirement Estimation Methods

Several different methods can be used to estimate amendment requirements. The overall framework is to estimate the amendment requirement based upon the volume and characteristics of the TTZ coupled with the demand from both background and contaminants within that TTZ. A quantitative approach is commonly a more effective basis for an initial estimate, which can then be refined and optimized based upon experience and/or pilot test results. Software modeling and amendment estimation tools are also available (see Section 3.3.1). Three methods can be used individually or in sequence:

- Method 1: Stoichiometric plus background calculation. The total amendment requirement is the sum of the demand from reaction with the estimated contaminant mass (e.g., from a stoichiometric degradation reaction) plus the demand from competing side reactions, such as with transition metals and/or natural organic carbon in the subsurface. This method is limited by the accuracy of contaminant mass estimates and the reactivity of the compounds that account for the competing side reactions.

- Method 2: Experienced based. Apply amendment loading rates that have been successful at other sites with similar geology, geochemistry, and plume characteristics. Although not as quantitatively supportable as Method 1, practitioner experience should not be discounted as an effective method to evaluate amendment requirements. However, all in situ remediation designs should be site-specific. Additionally, because many historical in situ remediation designs have not led to attainment of target end points, extreme care should be taken that practitioner experience that led to past failed application should not be the basis for future design.

- Method 3: Pilot test results. Perform a pilot test with an amendment dosing based on one of the above methods and use the resulting process and performance data to evaluate amendment requirements for future injections or a full-scale remedy.

Each of the methods outlined above is subject to significant uncertainty, thus incorporating a safety component is often prudent with amendment requirement estimates. After arriving at a conceptual design with one or more of the methods outlined above, evaluate the need for an additional safety factor to account for uncertainties such as degree of heterogeneity, accuracy of bench- and pilot-scale testing to full-scale site conditions, etc. (see Section 3.3.3). Amendments are the component of the remedy that ultimately result in subsurface treatment; however, amendments are often a relatively small component of overall project cost relative to other project management, labor, mobilization, equipment, and other costs. Read less

3.5.3 Volume Considerations

This section describes how to determine the overall volume of amendments, usually diluted in water that should be delivered. The considerations are fundamentally different depending on if the remediation program is designed to deliver a soluble amendment through pore space (injection of liquid) or to modify the subsurface permeability by pressurized application of a slurry (injection of a solid). Given these differences, discussion of volume delivered is subdivided below for injection of liquid versus injection of solids.

3.5.3.1 Volume for Liquid Injection

3.5.3.2 Volume for Solid or Slurry Injection

3.5.4 Amendment Persistence

The persistence of an amendment is based on the reagents (individual chemicals or component) that are used to make up the amendment and the amendment dose. Some very soluble or aqueous amendments, and the resulting benefit or reactions generated by the amendments, may persist for days, weeks, or perhaps a few months, due to the reactions and processes that consume the amendments. As a result, additional amendment injection events may be necessary to sustain an effective treatment. Examples of soluble amendments include certain organic carbon substrates such as lactate, certain chemical oxidants such as hydrogen peroxide, or a pH buffering aqueous solution such as sodium hydroxide. Other amendments are insoluble or sparingly soluble, and after emplacement will slowly release (via dissolution, hydrolysis, or other processes) dissolved-phase amendments over a much longer period of time, ranging from months to years or potentially decades. As a result, a desired subsurface geochemical condition or treatment zone can be maintained for a much longer period of time without additional injection. Many types of amendments are available in both very soluble and more insoluble forms (for example, sodium permanganate [soluble] and potassium permanganate [less soluble]), which provides flexibility and optimization of remedial designs for site-specific conditions.

3.6 Amendment Delivery Optimization

There is typically a trade-off between the number and spacing of direct push points/injection wells and the volume of amendment injected per point or well. There will likely be constraints on the budget, injection pressure, site access, time for implementation, and available mixing and distribution logistics and equipment. This represents an optimization opportunity where the minimization of cost or time needed for the successful completion of the project is subject to those constraints. The optimization may initially consider the trade-off of cost vs. time (see Section 2.1.2) and/or certainty of successful treatment for different delivery strategies (e.g., inject and drift vs. recirculation) (see below). Optimization may be more applicable, however, to the refinement of the number and spacing of injection points, injection transects, and recirculation wells for minimization of cost or time using one of the delivery strategies.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both direct push injection and injection wells. Injection wells are often used if there is a plan to do multiple rounds of injection over time or if long-term amendment addition is planned, because once installed, there is less need for remobilization of the more expensive equipment such as drill rigs. However, there is less flexibility with injection wells compared with direct push points because the injections occur over the same depth interval at the same location for each round. If direct push injections are used, there is flexibility to target hot spots or areas of rebound or to target different areas or depth intervals on subsequent rounds of injections, and there is less chance of fouling of the screen interval that can occur with injection wells over time. Consideration must be given to the planned duration of injections, access constraints, maintenance requirements, and the expected need for flexibility in injection layout over time when determining which injection method is preferred.

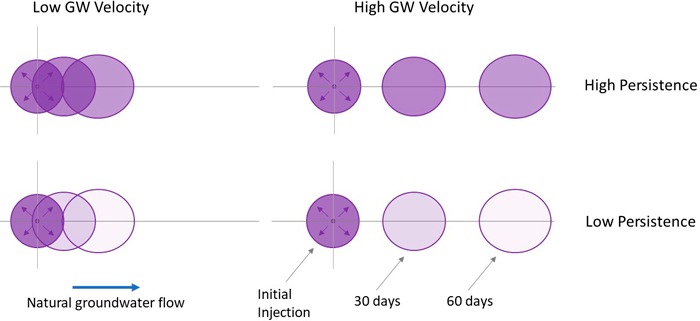

The optimization analysis requires information on the unit costs and time necessary for all activities related to the injection project, including well installation or direct push injection, field labor, sampling and analysis, equipment rental, storage of amendments and equipment, etc. The analysis also requires estimates of the time necessary for transport or delivery of amendments into and through the subsurface, given the hydrogeology of the site. Modeling and pilot testing will provide information on these aspects. As previously discussed in Section 3.5, the behavior and persistence of the amendment once injected must be understood and estimated. See Figure 3-2 for four examples of amendment persistence under natural flow (see Section 3.8). Finally, the client’s time and budget constraints, as well as other site physical and access constraints, must be considered.

Figure 3-2. Amendment persistence at natural flow using four scenarios.

Source: Graphic used with permission from Trihydro Corporation.

Each example in Figure 3-2 shows a plan view of one injection point, with natural groundwater flow transporting the amendment away from the injection location. The distribution of the amendment is shown over time, with lighter shaded circles indicating that the amendment is depleted or less effective. In areas with low groundwater flow, the amendment will be depleted before it can be transported downgradient. In an environment with higher groundwater velocity, the amendment is distributed farther from the injection point before it loses effectiveness

With this optimization analysis information, the cost and treatment time for different injection point/line spacing can be estimated. The costs included in the analysis should include the added monitoring, labor, reporting, etc., that would be necessary for a longer remedy implementation period and not just the time needed for the amendment delivery. The combination of injection point, line spacing, and amendment volume per point with the minimum time or cost that meets the project constraints would be preferred. Some assessment of the uncertainty in the success of the implementation is necessary to allow for some factor of safety in the selected design. An optimal arrangement is usually one that is very close to violating one of the constraints, so some conservatism is needed in the selected design.

Optimization can also be applied to the determination of the TTZ, when multiple technologies are used in different portions of the site or at different times (see Section 3.2.3). The optimization can be done in a way to achieve the fastest or least expensive overall remediation through a trade-off between the boundaries or timing of the various applications.

Formal optimization tools, when used with models, can automate the process of constructing the relationships between design parameters and cost and time. (see Section 3.3.1 for more information on modeling)

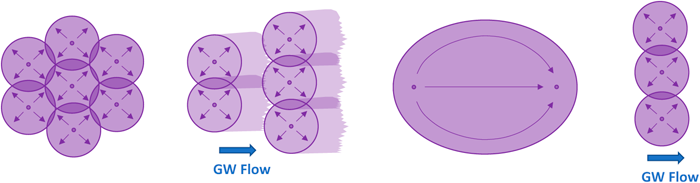

The strategy of amendment delivery refers to the high-level approach that will be applied to the TTZ. For example, for a TTZ within a predominantly low permeability geology, injection rates should reflect the geology (e.g., lower flow rates with a control on the injection pressure) to prevent unintentional fracturing, short-circuiting, or daylighting. Considerations include the desired outcome (e.g., source treatment versus mitigation of off-site impacts) and the amendment distribution mechanisms that will be used during and after delivery. Several types of strategies are described below and in Figure 3-3.

- Grid pattern: Perhaps the most common method of delivery is to space delivery locations uniformly over the treatment zone and to deliver amendment at each of these locations. This approach is based on (relatively) uniform delivery of amendment away from each delivery location and does not intend to leverage postinjection processes, such as adjective flow, to distribute the amendment within the TTZ. This approach is the most broadly applicable, i.e., there are very few site-specific constraints that would challenge this method.

- Inject and drift: This strategy leverages distribution of amendment with natural groundwater flow (the advective phase). The spacing of delivery locations is greater in the direction parallel to groundwater flow. This method is applicable in situations in which the amendment is soluble in water, groundwater velocities are relatively high, and/or the amendment is relatively persistent in the subsurface.

- Recirculation: This strategy consists of simultaneous injection and extraction of groundwater. This strategy can increase the lateral extent of amendment influence and reduce the risk of daylighting of amendment. Use of this strategy is typically limited to sites with relatively high transmissivity. Extraction and reinjection of contaminated groundwater can pose regulatory challenges, though (USEPA 2000) clearly stated that addition of an amendment that will result in treatment meets the requirement that contaminated groundwater be treated even if that treatment occurs after reinjection.

- Barrier: This strategy consists of delivery in a linear transect such that contaminated groundwater flows into the treatment zone where it is treated. Such strategies use a barrier to contaminant migration, but not to groundwater flow. Barrier strategies are applicable to continuous delivery systems (e.g., ozone sparging) or to sorptive or insoluble amendments.

Figure 3-3. Plan view of amendment delivery strategies (from left to right: grid pattern; inject and drift; recirculation; and barrier). Note that these graphics are schematic depictions and are not to-scale; in general, ROI are not circular or smooth-edged but variable due to heterogeneities in the subsurface. Barrier strategies may typically require double rows of delivery points, and recirculation systems often use more than a single injection and extraction well. For high seepage–velocity sites, distribution is less circular and more elongated and the lateral, cross-gradient extent of ROI at the injection location may not be achieved.

Figure 3-3. Plan view of amendment delivery strategies (from left to right: grid pattern; inject and drift; recirculation; and barrier). Note that these graphics are schematic depictions and are not to-scale; in general, ROI are not circular or smooth-edged but variable due to heterogeneities in the subsurface. Barrier strategies may typically require double rows of delivery points, and recirculation systems often use more than a single injection and extraction well. For high seepage–velocity sites, distribution is less circular and more elongated and the lateral, cross-gradient extent of ROI at the injection location may not be achieved.

Source: Graphic used with permission from Trihydro Corporation.

3.6.1 Overcoming Delivery Problems

Several factors can prevent optimal distribution of amendments. Poor estimates of required injection pressures or injection at higher than design rates to overcome poor distribution can prevent optimal amendment distribution or create preferential pathways, thereby not achieving uniform distribution in the TTZ. Fouling of the distribution pathways through biofouling, formation of inorganic precipitates, or gas build up reduces the permeability and can result in nonuniform distribution in the TTZ. Generally, fouling is a process in which a well screen, filter pack, and/or the surrounding formation become clogged over time. Fouling is most common for fixed injection wells, rather than direct push injection (DPI) (which can be repositioned if an area becomes fouled), especially if multiple injection events are required.

3.6.1.1 Injection Pressure versus Flow Rate

3.6.1.2 Biofouling

3.6.1.3 Fouling by Inorganic Precipitates

3.6.1.4 Gas Fouling

3.6.2 Prevention and Control of Biofouling

3.6.2.1 Design Considerations

3.6.2.2 Operational Strategies

3.7 Delivery Layout Design and Volume per Location

This section describes the methods for determining the number of delivery locations, their spacing, and how much volume to deliver at each location. The text in this section assumes that the following data have already been generated: RDC data (see Section 2); the preferred amendment type and general delivery method that emerged from screening (see Section 3.4); the definition of the TTZ (see Section 3.2.1); the mass of amendment required (see Section 3.5); the strategy for amendment delivery (see Section 3.6); and the overall volume of fluid to be delivered (see Section 3.5.3).

The number and spacing of injection locations should be based on the overall goal of achieving adequate distribution of amendment throughout the TTZ. Amendment will travel through the subsurface through the following processes subject to the constraints listed below.

- Advection as the result of pressurized delivery, i.e., physical displacement of pore water (for injection) or formation of new porosity as the result of fracturing (for emplacement). The primary constraints on advection during delivery are: (1) preferential flow through higher permeability zone, and (2) limitations on the volume injected and amount of time allotted for delivery. Transport of many amendments will be greatest during active injection.

- Advection due to natural groundwater flow, which can transport amendments additional distances after active delivery ceases. Constraints on ambient advection are: (1) the rate at which the amendment is depleted in the subsurface, (2) the propensity of the amendment to move with the groundwater or adhere to soil surfaces, and (3) preferential flow through higher permeability zones. The choice of the amendment will also impact the distribution. Soluble substrates should distribute farther than fine particles of emulsified vegetable oil (EVO) or large-scale particles of ZVI. The nature of the amendment will also impact transport, with nonionic particles less likely to react with charged soil particles than charged amendment particles.

- Diffusion as the result of concentration gradients, which is constrained by (1) amendment depletion in the subsurface, and (2) slow rates of diffusion.

3.7.1 Number of Delivery Locations and Volume for Injection of Liquids

3.7.2 Number of Delivery Locations and Volume for Injection of Slurries/Solids

3.8 Delivery Strategies

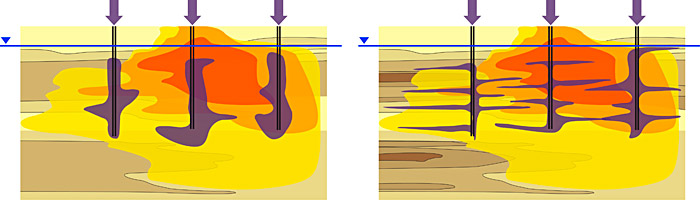

Whether via permanent, fixed points or temporary locations, amendment distribution through a porous aquifer media is controlled by the nature of the amendment (soluble, semisoluble, or insoluble), the permeability of the formation, the volume of amendment added, and the pressure at which the fluid is applied to the formation.

Advection-dominated transport controls the flow of groundwater, contaminants, and amendments. These high permeability zones often receive the most fluids, allow broadest radial delivery, and are therefore key to determining injection location spacing. As a result, these zones are often where the most rapid and extensive treatment gains can be achieved. Advection-dominated transport includes rock and soils with large hydraulic conductivity values (fractured limestones, gravels, sands), but can also zones of moderate relative permeability (silty sands, clayey sands) with slower rates of advection compared to storage zones dominated by diffusion (see Section 3.5.3.1). To avoid driving contamination outside the treatment area, it may be advantageous to begin injection near the fringe of the plume/aqueous phase and progress upgradient where multiple injections are required.

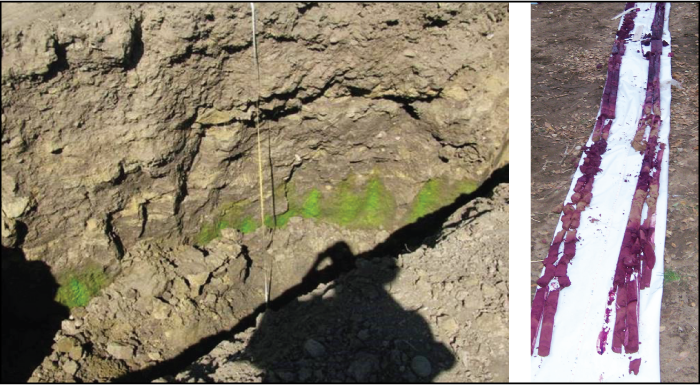

A variety of amendments are available to promote biological or chemical transformation, depending on the properties of a specific target contaminant. These amendments all have different chemical properties that control their introduction and transport through the subsurface and potentially limit the injection methods available. The particle size of many solid-phase amendments such as oxygen-releasing materials, ZVI, or activated carbon is larger than most pore throats and prevents delivery through well screens. High-pressure emplacement technologies using hydraulic or pneumatic methods are therefore required to deform the aquifer matrix and propagate seams (fractures) within the aquifer matrix. Conversely, soluble amendments like organic carbon substrates and chemical oxidants can be delivered under gravity flow or at low pressure via permanent or temporary well screens and via high-pressure fracturing methods.

Given that natural aquifer conditions control both contaminant and amendment transport, mapping the contaminant distribution within the aquifer architecture is key to determining what delivery approach to select. Wells and fracture-based injection points can both be successfully used for delivery through more permeable advective soils, but the applicability of injection wells declines as the matrix become less permeable. To address contaminants residing in lower hydraulic conductivity zones, fracturing technologies are used to propagate amendments at the desired target depth. In these cases, fractures are established to serve as new zones of higher permeability within the rock matrix. Amendments with greater longevity emplaced within these fractures can diffuse into lower permeability soils adjacent to the fracture and provide treatment of contaminants migrating from the low permeability zones into the new fracture interval.

Finally, injection method selection is determined based on site access constraints and remedial goals. For sites where only one injection or emplacement event is planned, or where the installation of permanent injection wells is infeasible, temporary injection points and emplacement-based methods are often preferred. When multiple injection events are expected and the rock matrix is more permeable or conducive to well-based delivery, it is often more economical to install permanent injection wells to reduce overall project life cycle cost.

3.8.1 Injection Screening Matrix

3.8.2 Material Compatibility and Other Safety Considerations

3.8.3 Implementation

Click here to download the entire document.